Marianna of Austria & Johann Nithard

How I found Marianna of Austria, and her Jesuit tutor, Johann Nithard who became my villain...

It was quite by chance that I came across Marianna of Austria. She was born in Vienna at the court of her paternal grandfather the Habsburg Emperor, Ferdinand II. Her father, who would become Emperor in 1637, was as yet only the King of Hungary and Bohemia, and was away for most of his wife's pregnancy campaigning in the Thirty Years' War. As a child, she was engaged to her Spanish Habsburg first cousin Baltasar Carlos, Prince of Asturias, but when he died aged 16 in 1646, King Philip IV of Spain was left without a male heir and Maria-Anna without a fiancé. In 1649, the king married his 14-year-old niece himself. Although known for being cheerful as a young girl, after her wedding to her uncle she became 'cold and bad-tempered'.

During her childhood, her tutor was the Austrian Jesuit, Johann Eberhard Nithard, and when she married Philip IV, he remained at her side as her confessor. When Philip died, Marianna became the Queen Regent for her son Carlos (later Charles II of Spain) who was too young and disabled to rule for himself. Nithard's power increased enormously when he was appointed Inquisitor General, the highest official authority in the Spanish Inquisition.

Eventually, Nithard's influence waned in favour of the Queen's new favourite, Fernando de Valenzuela, and following the overthrow of Marianna by John of Austria, he eventually became a cardinal in Rome, where he ended his life.

Those are a brief summary of the facts. What was more interesting to me was the unhappy marriage of convenience between the two Hapsburgs, Marianna and her uncle Philip, leading to the sad state of the inbred Charles II, the last of the Habsburg line. That this should be happening at the same time that piracy was increasing in the West Indies, and that the economy of Spain was in decline due largely to the country's absolute dependence on the riches being brought from the Americas brought even more pressure on the Queen Regent. Her absolute belief in the Pope's edict declaring the lands in the Americas to be Spain's sole possession prevented her from accepting the reality of the political situation in the Caribbean, and coming to terms with the other great powers who were intent on staking their own claims in the region.

It occurred to me that as an Austrian, Nithard would be less blinkered in his views than Marianna, and I therefore took it upon him to act as the voice of reason and political reality. With the increasing uncertainty of the supply of gold and silver from the New World, I felt it would have been clear to him that military action against the rest of the European powers was doomed - if only on economic grounds. That this should lead him to use less conventional means to destabilise the situation by bringing Henry Morgan's reputation into question seemed an obvious move, given the access to the network of spies and informers that his new position as Head of the Inquisition afforded him.

Henry Morgan acted to preserve his reputation against the English publishers of Exquemelin's book. But we know that the English edition was not the first one, and that Exquemelin himself did not understand the languages of the editions which preceded the English one. It therefore seemed reasonable to suppose that a process of chinese whispers could have occurred which manipulated the original to suit the political demands of each of the different national audiences for each of the translations of the book. It was a short step to seeing Nithard as the puppet master overseeing this manipulation, if not carrying it out himself - he would of course have spoken German and Spanish fluently.

So Nithard had the means, the motive and the opportunity. And that - in the world of my imagination, at least - gave me my villain.

Henry Morgan

So, I'd met my main character, Alexandre Exquemelin. And from hearing just a short account of his exploits during his time in the Caribbean, I realised that my hook into this story was Welshman, Henry Morgan.

But first, who was this Alexandre Exquemelin? Well, he’s the man who wrote the book on buccaneers. Literally. Exquemelin was the author of the first (and only) book written at the time about these men, by someone who shared their adventures with them. Exquemelin’s book, called (in English) The American Buccaneers, first published in 1678, has led to just about every other book and film about pirates – ever.

So what was this young student of medicine from France doing in brutal, lawless Tortuga as an indentured servant of the French West Indies Company? What made him give up six years of study to become (in effect) a slave? Was it because he was a Huguenot, persecuted by Catholic France? How did he come to join Henry Morgan, a Welsh soldier in the service of England?

Why did he write a book about the exploits of these people? Why was Henry Morgan brought back to London as a prisoner, but returned three years later with a knighthood, and a commission as Deputy Governor of Jamaica?

And why did the English version of Exquemelin’s book, translated from the Spanish, cause Henry Morgan to sue the English publishers for defamation of character?

From the court of the Inquisition to the cesspit of Tortuga, from the mangrove swamps and jungles of Panama to the royal courts of London and Madrid, with its mixture of high adventure and high politics, centred on real events and characters (who we may not know quite as well as we first thought), it seemed to me that this was a story that deserved to be told

And so to Henry Morgan. Henry Morgan, the pirate. Or was he?

Henry Morgan, the pirate. Captain Morgan Rum. Pirates of the Caribbean. Johnnie Depp. Captain Blood. Errol Flynn. Treasure Island. Robinson Crusoe. You know them all, don’t you? Seen the films, got the tee-shirt. Me, too. I knew all about pirates.

Until I discovered that I didn’t know the difference between a pirate and a privateer. Nor that the original boucaniers lived by killing and smoking wild boar over a fire pit.

I soon learned that there was a lot more to these ‘pirates’ than an undisciplined rabble of sea-borne cowboys, raping and plundering their way around the tourist spots of the Caribbean. There was more than a hint of international high politics.

But how could I avoid the romanticism and preconceptions that come with every account of pirates we come across? I was really lucky - I found a book, called Harry Morgan's Way, by Dudley Pope, that did just what I wanted. It told me all I needed to know about what really happened, and who Henry Morgan really was. I recommend it to anyone who wants to know the truth (or at least as much as we can ever know from a distance of three hundred years) of Henry Morgan's exploits.

How I met Alexandre

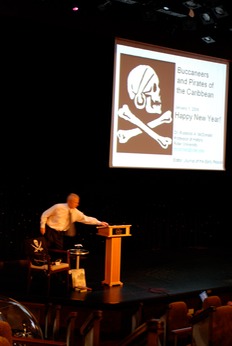

I would be unforgivable to forget the day I met him. It was New Year's Day, 2008, aboard the Cunard liner, Queen Mary 2, cruising majestically somewhere in the middle of the beautiful blue Caribbean.

What was his name? Almost unpronounceable, his name was Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin. And even though he had been dead over 300 years, he was as alive to me as if I had actually bumped into him. The man who introduced us (so to speak) was Professor Roderick McDonald of Rider University (New Jersey).

He had the unenviable task of giving a lecture at 10:00am on New Year’s Day, following the party-to-end-all-parties on board the QM2 the previous New Year’s Eve. Using the cunning ploy of calling his lecture ‘Buccaneers and Pirates of the Caribbean’, Professor McDonald ensured himself an audience, and I remember sitting fascinated by the information that he presented about that short period in history when pirates roamed the West Indies in search of plunder and wealth.

So who was this unpronounceable Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin?

He was the man who wrote the book about pirates. And that statement should be taken quite literally. He was the only person who witnessed the exploits of these men and wrote down what he saw in a book, published under the English title of ‘The American Sea-Rovers’. Just about everything we know about pirates started with this unique book. So when I say that he was the man who wrote the book, it’s quite literally true.

I had for some time been looking for a subject to write about which would combine a world perspective with something local to where I live in South Wales. And when I learned that Monsieur Exquemelin had sailed with the infamous Henry Morgan, I realised that I had found my subject.

Henry Morgan had been born not more that a few miles from where I live, and had lived to acquire his ferocious reputation through his exploits during the sacking of Puerto Principe, Maracaibo and most significantly, the old city of Panama, none of which were more than a few hundred miles from where we floated that morning in the Caribbean.

So, a big thank you to Professor McDonald for introducing me to my enigmatic Frenchman - I'm so glad I made it to his lecture that morning.